Migration in today’s world is a complex phenomenon that can have both positive and negative impact: a smart and flexible migration policy can help countries strengthen their social, economic and political ties and open up new sources of capital and investment. In contrast, an irrational and excessively restrictive migration policy can cause imbalances in the labour market and income inequalities between immigrants and local residents, potentially leading to high levels of social tension.

The number of international migrants is estimated to be almost 272 million globally, or 3.5% of the world’s population. They live, work, pay taxes, start families and raise children outside of their countries of origin. Post-Soviet countries are no exception. In 2019, Russia, Kazakhstan and Ukraine were among the world’s top twenty origin and destination countries for migrants.

In the context of the Western classification of countries into nations of immigrants, countries of immigration and latecomers to immigration, 1 Hollifield, J. F., Martin, P. L., & Orrenius, P. M. (2014): Controlling immigration: A global perspective. Stanford: Stanford University Press the independent states of the former USSR can be described as “countries of destination which have yet to fully embrace migrants’ potential” (Russia and Kazakhstan) and “countries caught in an emigration trap and struggling, with varying degrees of success, to become independent from emigration” (Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, Moldova, Armenia and Uzbekistan). It is imperative for each of the post-Soviet countries – and especially for Russia as the main centre of attraction for post-Soviet migrants – to reflect on what migration means for them: is it a burden or an opportunity?

Migration to Russia, in numbers

Studies focusing on the economic aspects of migration have been very popular in the West. In his book Immigration Economics, George Borjas explains how the economic laws of supply and demand determine a country’s migration success. 2 Borjas, George J. (2014): Immigration Economics. Harvard University Press Khalid Koser examines the impacts of both legal and undocumented immigration and concludes that migration, as an ever-growing form of human mobility, has a great financial future before it. 3 Khalid Koser (2007): International Migration: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford So far, however, few people in the post-Soviet space, including both Russia and Kazakhstan, support the idea that without restrictions hindering human mobility, the world would be better off financially and more diverse ethnically.

Russia receives the largest number of migrants from the independent states built on the ruins of the former USSR. Most of these migrants flock to Russia in search of employment and income. Russia is faced with both pros and cons of this migration inflow, which can be expressed in numbers.

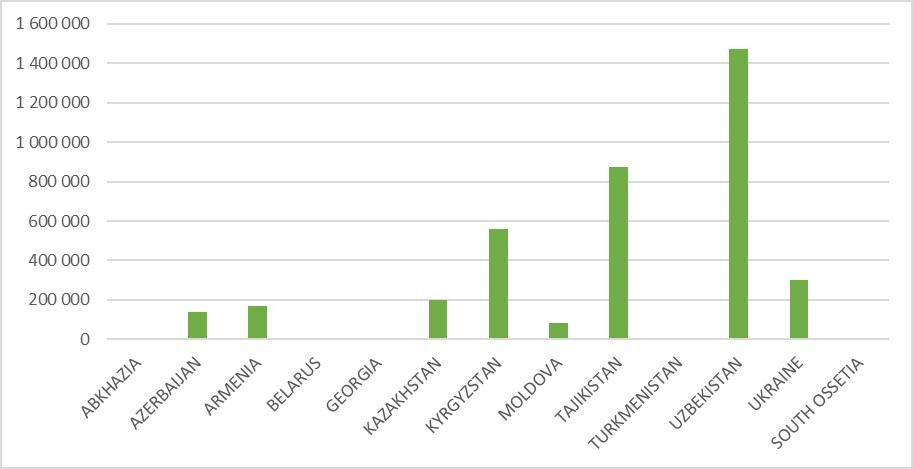

According to statistics from the Russian Border Service, a total of 3.8 million citizens of post-Soviet states entered Russia as labour migrants in 2019, of whom almost 1.5 million came from Uzbekistan, 875,000 from Tajikistan, and 558,000 from Kyrgyzstan. Nations such as Ossetians (5), Abkhazians (8), Georgians (961) and Turkmens (1232) appear to be the least interested in Russia’s labour market.

In the first three quarters of 2019, remittances sent by migrants from Russia to their home countries totalled US$ 30,806 million. As before, most remittances were sent to the countries of Central Asia: Uzbekistan (US$ 3,496 million), Tajikistan (US$ 1,941 million) and Kyrgyzstan (US$ 1,460 million). These countries’ heavy reliance on remittances has its downside. Migrant remittances, coming mainly from Russia, make up a substantial share of some post-Soviet countries’ GDP, in particular: 33.6% of Kyrgyzstan’s GDP; 31% of Tajikistan’s GDP; 16.1% of Moldova’s GDP; 12.1% of Armenia’s GDP; 11.4% of Ukraine’s GDP, and 9% of Uzbekistan’s GDP.

All of these countries – suppliers of migrants – are effectively caught in the “emigration trap.” First, they risk losing their demographic and labour potential and becoming overdependent on socioeconomic and political processes in country of destination (in this case, Russia). Second, the exchange rates of these countries’ (specifically, Kyrgyzstan’s and Tajikistan’s) national currencies are overestimated, while their export demand is underestimated. 4 Eromenko, Igor (2016): Do Remittances Cause Dutch Disease in Resource Poor Countries of Central Asia? Published in: Central Asia Program Economic Papers Series, Elliott School of International Affairs, George Washington University No. Central Asia Program Economic Papers Series No. 18 (January 2016) All of these are negative consequences of the “emigration trap.”

But migrants send only part of their earnings as remittances to their home countries. As for the other part, often far exceeding the remittance amounts, most migrants spend it in the host country to pay for accommodation, food, legal assistance and paperwork, social, medical and other needs. 5 Рязанцев С.В., Сигарева Е.П. 2016. Демографические, социально-экономические и политические последствия миграционных процессов для Российской Федерации. Региональные проблемы преобразования экономики. № 3(65). С. 94-102.

The remittance outflow caused by labour migrants does not have a significant impact on Russia’s financial system: in 2017, the ratio of outgoing remittances to its GDP was insignificant at just 1.3%. Moreover, all countries which supply labour migrants and receive remittances consider Russia their main trading partner, adding to Russia’s geopolitical and economic gains from migration.

Migrants, however, do not only contribute to their countries’ GDPs by sending money home. They also serve as a source of income for many parts of Russia by paying the costs of their labour patents to regional budgets. In 2018, Russian regions received a total of 58.3 billion rubles (0.85 million euros) in labour patent fees, of which 17.5 million rubles went to the city of Moscow, 8.3 million rubles to the Moscow region, and 7.3 million rubles to the city of St. Petersburg. In the nine months of 2019, the city of Moscow received 13.2 billion rubles (0.184 million euros) in labour patent fees paid by migrants (1.7% increase compared to the same period of 2018).

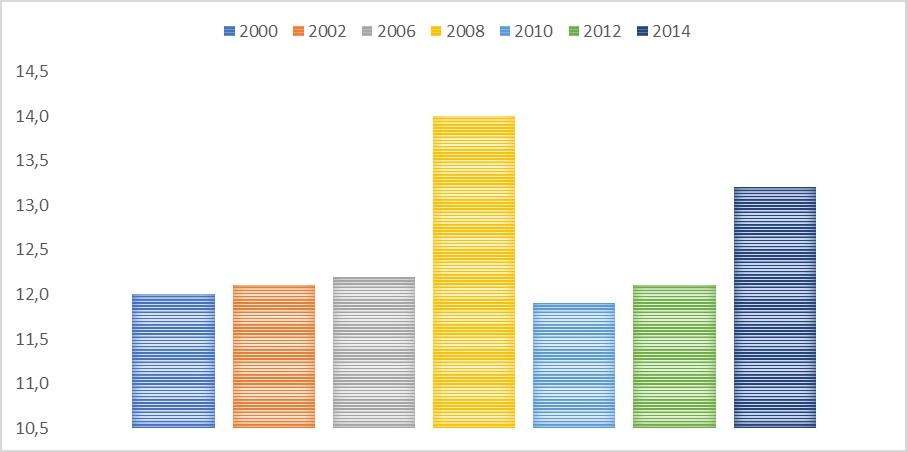

According to experts, labour migrants’ contributions to Russia’s GDP form an upward curve with values ranging from 10% to 13.2% of the GDP. In addition to this, the inflow of migrants has a positive effect on the GRP (gross regional product) of certain Russian regions by contributing up to 4%. 6 World Bank. (2009). Free International Migration Works: Immigrants’ Contribution to Economic Growth of Russian Regions.

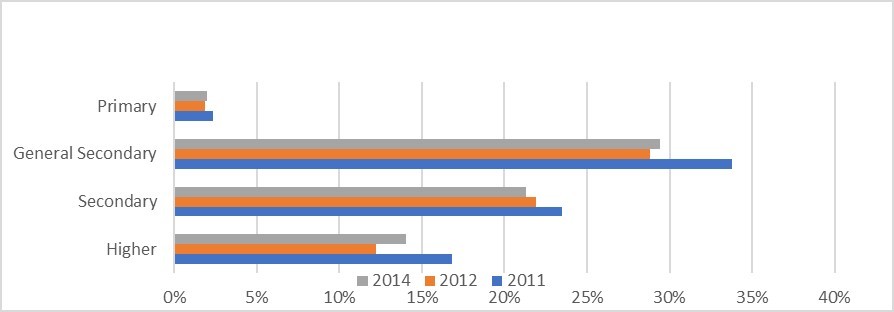

Academic researchers in the West have long proved that an inflow of migrants can increase the size of the host country’s economy within a short period of time, i.e. immigration can be a source of extensive economic growth. 7Cattaneo, C., Fiorio, C.V., Peri, G., 2013. What Happens to the Careers of European Workers when Immigrants “Take Their Jobs”? IZA Discussion Paper 7282, IZA Institute for the Study of. Labor, Bonn But there is an important caveat, though. Only skilled immigrants with qualifications and/or work experience can produce this effect over a short term. An OECD paper reveals that it can take quite a while before younger, less skilled labour immigrants will start contributing more the host country than it has spent on them. 8 OECD (2014): Is Migration Good for Economy. Migration Policy Debate. May, 2014 The level of educational attainment of labour migrants coming to Russia has declined over the recent years, with fewer incoming migrants having higher education or vocational training and more having completed only secondary or even primary school. Today, this is perhaps is the strongest argument voiced by opponents of a more liberal migration management in Russia.

Migrants in the host country are taxpayers and producers, as well as consumers, of goods and services. Unfortunately, no studies have yet examined the purchasing power of the millions of labour migrants coming to Russia. But in Austria, migrants’ purchasing power has been estimated at 20 billion euros, exceeding the revenues brought by foreign tourists (16 billion euros).

Migration in Russia and in the broader post-Soviet space is a social process ruled by the logic of economic laws. Migrants contribute to host country economies and stabilise their socio-demographic potential; therefore, Russia and other independent post-Soviet states need to move away a false perception of migrants as being “a burden and a threat” towards seeing them as a source of opportunity and potential.

Similar Posts:

References

| ↑1 | Hollifield, J. F., Martin, P. L., & Orrenius, P. M. (2014): Controlling immigration: A global perspective. Stanford: Stanford University Press |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Borjas, George J. (2014): Immigration Economics. Harvard University Press |

| ↑3 | Khalid Koser (2007): International Migration: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford |

| ↑4 | Eromenko, Igor (2016): Do Remittances Cause Dutch Disease in Resource Poor Countries of Central Asia? Published in: Central Asia Program Economic Papers Series, Elliott School of International Affairs, George Washington University No. Central Asia Program Economic Papers Series No. 18 (January 2016) |

| ↑5 | Рязанцев С.В., Сигарева Е.П. 2016. Демографические, социально-экономические и политические последствия миграционных процессов для Российской Федерации. Региональные проблемы преобразования экономики. № 3(65). С. 94-102. |

| ↑6 | World Bank. (2009). Free International Migration Works: Immigrants’ Contribution to Economic Growth of Russian Regions. |

| ↑7 | Cattaneo, C., Fiorio, C.V., Peri, G., 2013. What Happens to the Careers of European Workers when Immigrants “Take Their Jobs”? IZA Discussion Paper 7282, IZA Institute for the Study of. Labor, Bonn |

| ↑8 | OECD (2014): Is Migration Good for Economy. Migration Policy Debate. May, 2014 |