Under the European Convention on Human Rights, states must guarantee free and open debates about the past. Yet, with the rise of memory laws, the right to free expression has been endangered.

The Rise of Memory Laws

Member states of the Council of Europe (CoE) have been attempting to shape personal and collective historical memory through various policy tools, including legal prohibitions. Imposing official narratives and evaluations of the past and restricting what can be said about history have been traditional prerogatives of political authorities. Today, international human rights law, especially the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), has set limits on this authority. 1European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, as amended by Protocols Nos. 11and 14, 4 November 1950 However, in the past decade, we have observed an increased interest on the part of many CoE states in enacting specific criminal prohibitions on certain expressions about the past, the so-called memory laws. 2Nikolay Koposov, Memory Laws, Memory Wars: The Politics of the Past in Europe and Russia (Cambridge University Press, 2017), p. 8; Aleksandra Gliszczyńska-Grabias, “Memory Laws or Memory Loss? Europe in Search of Its Historical Identity through the National and International Law,”Polish Yearbook of International Law 34 (2014): 161. Such regulations raise doubts about whether they are compatible with ECHR standards for freedom of expression.

For instance, in 2014, Russia introduced an “act against exonerating Nazism” that outlaws discussing the flagrant human rights violations and war crimes committed by the Red Army. 3See O.G. Karpovich, “The Yarovaya Package and the Patriot Act: A Comparative Analysis,” Law and Legislation 9 (2016): 15–18 (in Russian). In 2016, Ukraine adopted a series of “de-communisation” laws, including an act condemning the Communist and Nazi regimes and prohibiting promotion of their symbols. 4See European Commission for Democracy Through Law (Venice Commission) and OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR), “Joint Interim Opinion on the Law of Ukraine on the Condemnation of the Communist and National Socialist (Nazi) Regimes and Prohibition of Propaganda of Their Symbols.” Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 105th Plenary Session Venice (18–19 December 2015). In January 2018, Poland made it a crime to accuse the Polish state and nation of certain crimes that occurred during the Second World War. The Polish parliament repealed the law in June 2018. 5See Aleksandra Gliszczyńska-Grabias, Grażyna Baranowska, and Anna Wójcik, “Law-Secured Narratives of the Past in Poland in Light of International Human Rights Law Standards,”Polish Yearbook of International Law 38 (2018): 59–72. In early 2020, Lithuanian lawmakers began drafting a resolution declaring that during the Soviet occupation, from 1940 to 1990, Lithuania and its government were not involved in perpetrating the Holocaust, because the country was occupied during this time.

There is no binding definition of memory laws in international law, European Union (EU) law, or the domestic law codes of CoE states. However, this concept has been firmly established in the academic literature and has been invoked in the United Nations Human Rights Committee’s proceedings, in documents published by the CoE, 6Council of Europe, “‘Memory Laws’ and Freedom of Expression. Thematic Factsheet (Update: July 2018).” and in reports prepared by human rights NGOs. 7“Submission to the Universal Periodic Review of Spain by ARTICLE 19 and the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF). For consideration at the 35th Session of the Working Group in January 2020, [dated]18 July 2019.” It has also figured in public debates. 8Eric Heinze, “Should governments butt out of history?” Free Speech Debate, 12 March 2019.

The CoE defines “memory laws” as norms that “enshrine state-approved interpretations of crucial historical events and promote certain narratives about the past, by banning, for example, the propagation of totalitarian ideologies or criminalising expressions which deny, grossly minimise, approve or justify acts constituting genocide or crimes against humanity, as defined by international law.” 9Council of Europe, “‘Memory Laws’ and Freedom of Expression.”

The term loi mémorielle originally referred to the French criminal ban on Holocaust denial, introduced in 1990 under the Gayssot Law. 10Françoise Chandernagor, “L’enfer des bonnes intentions,” Le Monde, 16 December 2005. Today, Holocaust denial bans are common in the CoE states. Some states have also enacted denial bans regarding other genocides and crimes against humanity. There are also prohibitions on promoting fascism and totalitarianism, including by displaying their symbols. Other examples of memory laws are regulations protecting historical symbols, laws protecting the reputation of historical figures, bans on insulting state and nation by certain expressions concerning the past and history, and bans on commemorating and mourning historical events.

The European Convention on Human Rights

International human rights law provides firm grounds for evaluating various memory laws. 11Anna Wójcik, “European Court of Human Rights, freedom of expression and debating the past and history,” Problemy Współczesnego Prawa Międzynarodowego, Europejskiego i Porównawczego 17 (2019): 33–46. The freedom of expression, enshrined in Article 10 of the ECHR, and necessary and proportional limitations to it, as interpreted by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in its case law, frame the discussion on memory laws. Crucially, the ECtHR has ruled that Article 17 of the ECHR (prohibition of abuse of rights) removes certain expressions from the protections of Article 10. These are expressions that are gratuitously offensive or insulting, inciting disrespect or hate; those casting doubt on clearly established historical facts; and expressions that are tantamount to the glorification of or incitement to violence. 12See Council of Europe, “Hate Speech, Apology of Violence, Promoting Negationism and Condoning Terrorism. Thematic Factsheet (Update: July 2018).”

Expressions about the past and history also fall into these three categories. For example, the ECtHR found that calling a person in Germany a “Nazi” without any relevant link to the person’s actions is a form of insult. 13Wabl v. Austria, App. no. 24773/94 (ECtHR, 4 March 1998). Moreover, the ECtHR has argued that restrictions on the freedom of expression are a legitimate and necessary reaction to deliberate and conscious distortions of the historical truth. Notably, Holocaust denial is excluded from the protections of Article 10, even when the expression is not an incitement to violence or a threat to public order or the rights and reputations of others. But the ECtHR has until now argued that denial of other historical crimes is not protected under Article 10 only when the expression includes elements of an incitement to violence, or otherwise threatens the public order or the rights and reputations of others.

Consequently, the ECtHR has consistently ruled that criminal convictions under Holocaust denial bans in Germany conform to the ECHR. 14Witzsch v. Germany (2), App. no. 7485/03 (ECtHR, 13 December 2005); Williamson v. Germany, App. no. 64496/1 (ECtHR, 31 January 2019); Pastörs v. Germany, App. no. 55225/14 (ECtHR, 3 October 2019). But it has found that a conviction under the criminal ban on genocide denial in Switzerland for publicly denying that massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in 1915–1916 were genocide was a breach of Article 10 of the ECHR. 15Perincek v. Switzerland, App. no. 27510/08 (ECtHR, 10 October 2015). The ECtHR also ruled that the ECHR does not protect promoting the return of Nazism through publications, paramilitary exercises involving the use of Nazi uniforms and slogans, demonstrations celebrating Hitler’s birthday, or other public events involving the glorification of the rulers of the Third Reich and its army. 16Kühnen v. Federal Republic of Germany, App. no. 12194/86 (ECtHR, 12 May 1985); Ochensberger v. Austria, App. no. 21318/93 (ECtHR, 2 September 1994); Schimanek v. Austria, App. no. 32307/96 (ECtHR, 1 February 2000). However, in cases concerning the use of communist symbols, the ECtHR has emphasised that domestic courts must in each case take into account all relevant circumstances of the case in order to decide whether the public presentation of a symbol is a form of the outlawed promotion of an undemocratic political regime, and that courts must be aware that some symbols carry multiple meanings. The ECtHR found, for example, that the conviction in Hungary of a left-wing politician for publicly displaying a red star was in breach of Article 10. 17Vajnai v. Hungary, App. no. 33629/06 (ECtHR, 8 July 2008).

However, the ECtHR has also frequently highlighted the positive obligations of states to assure conditions for open and dispassionate debates about the past. 18Monnat v. Switzerland, App. no. 73604/01 (ECtHR, 21 December 2006). It has emphasised that historical events and historical figures must be open to scrutiny and criticism, as they present a matter of general interest for society. 19Dzhugashvili v. Russia, App. no. 41123/10 (ECtHR, 9 December 2014). The ECtHR has ruled that states must not restrict historical debates, especially on war crimes, genocide, or crimes against humanity, 20Fatullayev v. Azerbaijan, App. no. 40984/07 (ECtHR, 22 April 2010); Janowiec v. Russia, App. nos. 55508/07 and 29520/09, para. 187 (ECtHR, 23 October 2013); Orban et al. v. France, App. No. 20985/05, para. 46 and 47 (ECtHR, 15 January 2009). and other aspects of history, such as the lives of prominent historical figures. 21Constantinescu v. Romania, App. no. 32563/04 (ECtHR, 11 December 2012). To be compliant with ECHR standards, any provision of law that fulfills the criteria of a memory law must pass the test of legality, necessity, and proportionality.

Memory Laws and Other Restrictions on Freedom of Expression in Russia

To assess whether a state assures a free and open debate on the past, we must take into account the wider framework for freedom of expression. Expressions about history deemed “erroneous” by the state can also be effectively persecuted under prohibitions against insulting the state, its executive, legislative and judicial organs, or the nation, under bans on promoting fascism, and other forms of political extremism, under anti-terrorist laws and the like. Indeed, this is the case in Russia.

In his seminal book Memory Laws, Memory Wars, the Russian historian Nikolay Koposov presents a genealogy of regulations and laws enshrining official narratives about the past and restricting or outright banning competing, alternative historical accounts in post-Soviet Russia. 22Koposov, Memory Laws, pp. 207-299. After 1991, Russia adopted declaratory laws commemorating victims of totalitarian regimes, established new holidays, and erected memorials. Provisions introduced to the new penal code in 1996 prohibit manifestations of fascism and other forms of political extremism. To a significant extent, these regulations were modeled on the activist provisions typical of the democracies in Western Europe. Since the 1990s, many states in the CoE have decided that revisionism and denialism are persistent and pervasive social ills that should be dealt with under criminal law. In the 2000s, attempts were made to accommodate bans on the denial of historical atrocities to the Russian context.

Since 2010, freedom of expression in Russia has become ever more restricted. In 2013, a criminal ban on publicly disparaging society and insulting the religious feelings of believers was adopted. 23Federal Law No. 136-FZ of 29 June 2013 (On Amendments to Article 148 of the Russian Federation Criminal Code and Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation in the Aim of Protecting Religious Convictions and Feelings of Citizens Against Insults). In the same year, Russia passed a law permitting authorities to block websites that incite people to participate in riots, extremist activities, or unsanctioned public assemblies. In 2017, this law was amended, allowing authorities to block access to the websites of foreign or international NGOs. 24Federal Law No. 274-FZ of 21 July 2014 (Оn the Introduction of Changes to Article 280.1 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation). Importantly, since 2012, officially registered independent non-commercial organisations that receive funding from abroad and participating in political activities have been officially labeled “foreign agents” in Russia. 25Federal Law No. 121-FZ of 20 July 2012 (On the Introduction of Amendments to Various Legislative Acts of The Russian Federation Concerning Regulating the Activities of Non-Commercial Organisations Fulfilling the Functions of Foreign Agents). This has included International Memorial, a historical and human rights organisation that has been documenting the crimes of Stalinism and educating the Russian public about them. Since 2018, the “foreign agent” label has also been applied selectively to media outlets. 26OSCE, “Broadening of ‘foreign agents’ status for media in Russia detrimental to freedom of expression online, says OSCE Representative,” 26 January 2018.

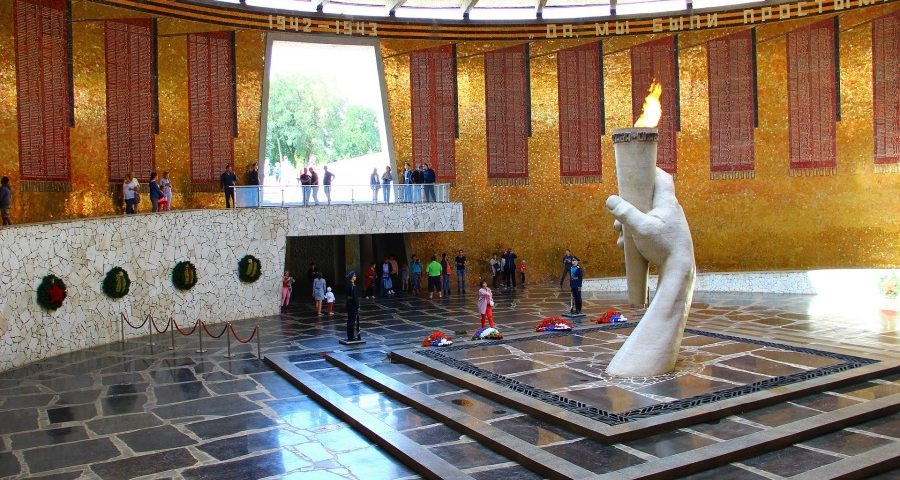

In 2014, a new memory law was introduced: Article 354.1 of the Criminal Code prohibits the “exoneration of Nazism,” as well as “dissemination of false information about the activities of the Soviet Union during the Second World War” and “desecration of symbols of military glory.” More specifically, it prohibits “denying the facts recognised by the international military tribunal that convicted and punished the major war criminals of the European Axis countries, to approve of the crimes this tribunal condemned, and to spread intentionally false information about the Soviet Union’s activities during World War II,” as well as “disseminating information on military and memorial commemorative dates related to Russia’s defense that is disrespectful of society, and desecrating symbols of Russia’s military glory publicly.” 27Ivan Kurilla, “The Implications of Russia’s Law against the ‘Rehabilitation of Nazism,’” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo, No. 331 (August 2014). The law is aimed at entrenching the grand narrative about the “Great Patriotic War” in Russia and countering historical narratives in countries formerly incorporated into or controlled by the Soviet Union, according to which they were victims of Soviet domination and occupation.

Most recently, on 3 July 2020, numerous amendments to the Russian Constitution were signed into law. 28See Johannes Socher, “Farewell to the European Constitutional Tradition: The 2020 Russian Constitutional Amendments,” Verfassungsblog, 2 July 2020. Article 67 proclaims that the state protects the “historical truth,” thus incorporating into the constitution what before was a legal norm. In 2016, the Russian Supreme Court upheld the conviction of a Russian national, under Article 354.1 of the Criminal Code, for saying that Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia had cooperated and attacked Poland in 1939. 29Gleb Bogush and Ilya Nuzov, “Russia’s Supreme Court Rewrites History of the Second World War,” EJIL:Talk!, 28 October 2016. While the brief alliance between Nazi German and the Soviet Union is a recognised fact in international historiography, it has been firmly denied in Russia’s official historical policy. According to the new official Russian narrative, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, concluded on 23 August 1939 between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, should be seen as a triumph of Soviet diplomacy.

The legal crackdown on freedom of expression in Russia is incompatible with international human rights law on freedom of expression, a concern raised in numerous reports prepared by human rights monitoring bodies, including the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission and NGOs such as the International PEN Club. 30European Commission for Democracy Through Law (Venice Commission), Opinion No. 981/2020, 18 June 2020, “Russian Federation. Opinion on the Draft Amendments to the Constitution of the Russian Federation (Signed by the President of the Russian Federation on 14 March 2020) Relating to the Execution in the Russian Federation of Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights.” Specific memory laws—such as the changes to Russian criminal code adopted in 2014 and the constitutional amendments enacted in 2020—are threads in a more vibrant tapestry of regulations.

Russia’s Memory Wars

Russia’s memory laws have attracted considerable attention worldwide, especially when they have provoked significant international repercussions. While their applicability to individuals outside of Russia is negligible, they are essential tools in Russian foreign policy.

In recent years, Russia has been involved in numerous high-profile memory wars with individual Central and Eastern Europe states and the European Union over conflicting interpretations of history. The 2014 Russian memory law buttresses an official narrative about the Red Army’s “liberation” of present-day Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia from fascism. This narrative has been firmly rejected by these states to the extent that the preambles to the democratic constitutions of Latvia and Estonia condemn the period of Soviet dominance as an occupation that included war crimes and human rights violations such as mass deportations. 31Cynthia M. Horne and Lavinia Stan, eds., Transitional Justice and the Former Soviet Union: Reviewing the Past, Looking Toward the Future (Cambridge University Press, 2018); Eva-Clarita Pettai, “Prosecuting Soviet genocide: comparing the politics of criminal justice in the Baltic states,” European Politics and Society 18.1 (2017): 52–65. Ukraine has also strongly condemned the period of Soviet dominance by enacting its own memory laws, including a law recognising the Holodomor as a deliberate Soviet genocide of the Ukrainian people, a series of “decommunisation” laws, 32Law No. 2538–1 (On the Legal Status and Honoring of Fighters for Ukraine’s Independence in the Twentieth Century); Law No. 2558 (On Condemning the Communist and National Socialist (Nazi) Totalitarian Regimes and Prohibiting Propaganda of Their Symbols); Law No. 2539 (On Remembering the Victory over Nazism in the Second World War); and Law No. 2540 (On Access to the Archives of Repressive Bodies of the Communist Totalitarian Regime from 1917–1991). such as the law prohibiting commemorating the Second World War with the St. George’s Ribbon, which is seen as a symbol of Soviet dominance. 33Ilya Nuzov, “Freedom of Symbolic Speech in the Context of Memory Wars in Eastern Europe,” Human Rights Law Review 19.2 (June 2019): 231–253.

The most recent “memory war” involving Russia followed the European Parliament’s resolution “on the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe,” adopted in September 2019. 34“European Parliament resolution of 19 September 2019 on the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe (2019/2819(RSP) ).” In 2020, as part of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the end of the Second World War, Russian President Vladimir Putin publicly blamed Polish officials for siding with the Nazis before the Second World War and for pre-war anti-Semitism in Poland. Immediately, the European Commission announced an EU joint position that no such distortions of historical facts would be tolerated and that any false claims attempting to distort the history of the Second World War or paint the victims, such as Poland, as perpetrators would be rejected. 35Jan Strupczewski, “EU raps Russia for saying Poland helped start World War Two,” Reuters, 15 January 2020. In the first half of 2020, the coronavirus pandemic overshadowed this diplomatic conflict. However, the July amendments to the Russian Constitution are a forceful assertion that protecting what the Russian authorities understood as “historical truth” remains a policy priority for the Kremlin, despite being subjected to mounting criticism by the Russia’s international partners and international human rights lawyers.

The proliferation of memory laws means that we should consider different regulatory responses to the need for protecting historical truth in the various member states of the Council of Europe.

Similar Posts:

References

| ↑1 | European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, as amended by Protocols Nos. 11and 14, 4 November 1950 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Nikolay Koposov, Memory Laws, Memory Wars: The Politics of the Past in Europe and Russia (Cambridge University Press, 2017), p. 8; Aleksandra Gliszczyńska-Grabias, “Memory Laws or Memory Loss? Europe in Search of Its Historical Identity through the National and International Law,”Polish Yearbook of International Law 34 (2014): 161. |

| ↑3 | See O.G. Karpovich, “The Yarovaya Package and the Patriot Act: A Comparative Analysis,” Law and Legislation 9 (2016): 15–18 (in Russian). |

| ↑4 | See European Commission for Democracy Through Law (Venice Commission) and OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR), “Joint Interim Opinion on the Law of Ukraine on the Condemnation of the Communist and National Socialist (Nazi) Regimes and Prohibition of Propaganda of Their Symbols.” Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 105th Plenary Session Venice (18–19 December 2015). |

| ↑5 | See Aleksandra Gliszczyńska-Grabias, Grażyna Baranowska, and Anna Wójcik, “Law-Secured Narratives of the Past in Poland in Light of International Human Rights Law Standards,”Polish Yearbook of International Law 38 (2018): 59–72. |

| ↑6 | Council of Europe, “‘Memory Laws’ and Freedom of Expression. Thematic Factsheet (Update: July 2018).” |

| ↑7 | “Submission to the Universal Periodic Review of Spain by ARTICLE 19 and the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF). For consideration at the 35th Session of the Working Group in January 2020, [dated]18 July 2019.” |

| ↑8 | Eric Heinze, “Should governments butt out of history?” Free Speech Debate, 12 March 2019. |

| ↑9 | Council of Europe, “‘Memory Laws’ and Freedom of Expression.” |

| ↑10 | Françoise Chandernagor, “L’enfer des bonnes intentions,” Le Monde, 16 December 2005. |

| ↑11 | Anna Wójcik, “European Court of Human Rights, freedom of expression and debating the past and history,” Problemy Współczesnego Prawa Międzynarodowego, Europejskiego i Porównawczego 17 (2019): 33–46. |

| ↑12 | See Council of Europe, “Hate Speech, Apology of Violence, Promoting Negationism and Condoning Terrorism. Thematic Factsheet (Update: July 2018).” |

| ↑13 | Wabl v. Austria, App. no. 24773/94 (ECtHR, 4 March 1998). |

| ↑14 | Witzsch v. Germany (2), App. no. 7485/03 (ECtHR, 13 December 2005); Williamson v. Germany, App. no. 64496/1 (ECtHR, 31 January 2019); Pastörs v. Germany, App. no. 55225/14 (ECtHR, 3 October 2019). |

| ↑15 | Perincek v. Switzerland, App. no. 27510/08 (ECtHR, 10 October 2015). |

| ↑16 | Kühnen v. Federal Republic of Germany, App. no. 12194/86 (ECtHR, 12 May 1985); Ochensberger v. Austria, App. no. 21318/93 (ECtHR, 2 September 1994); Schimanek v. Austria, App. no. 32307/96 (ECtHR, 1 February 2000). |

| ↑17 | Vajnai v. Hungary, App. no. 33629/06 (ECtHR, 8 July 2008). |

| ↑18 | Monnat v. Switzerland, App. no. 73604/01 (ECtHR, 21 December 2006). |

| ↑19 | Dzhugashvili v. Russia, App. no. 41123/10 (ECtHR, 9 December 2014). |

| ↑20 | Fatullayev v. Azerbaijan, App. no. 40984/07 (ECtHR, 22 April 2010); Janowiec v. Russia, App. nos. 55508/07 and 29520/09, para. 187 (ECtHR, 23 October 2013); Orban et al. v. France, App. No. 20985/05, para. 46 and 47 (ECtHR, 15 January 2009). |

| ↑21 | Constantinescu v. Romania, App. no. 32563/04 (ECtHR, 11 December 2012). |

| ↑22 | Koposov, Memory Laws, pp. 207-299. |

| ↑23 | Federal Law No. 136-FZ of 29 June 2013 (On Amendments to Article 148 of the Russian Federation Criminal Code and Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation in the Aim of Protecting Religious Convictions and Feelings of Citizens Against Insults). |

| ↑24 | Federal Law No. 274-FZ of 21 July 2014 (Оn the Introduction of Changes to Article 280.1 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation). |

| ↑25 | Federal Law No. 121-FZ of 20 July 2012 (On the Introduction of Amendments to Various Legislative Acts of The Russian Federation Concerning Regulating the Activities of Non-Commercial Organisations Fulfilling the Functions of Foreign Agents). |

| ↑26 | OSCE, “Broadening of ‘foreign agents’ status for media in Russia detrimental to freedom of expression online, says OSCE Representative,” 26 January 2018. |

| ↑27 | Ivan Kurilla, “The Implications of Russia’s Law against the ‘Rehabilitation of Nazism,’” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo, No. 331 (August 2014). |

| ↑28 | See Johannes Socher, “Farewell to the European Constitutional Tradition: The 2020 Russian Constitutional Amendments,” Verfassungsblog, 2 July 2020. |

| ↑29 | Gleb Bogush and Ilya Nuzov, “Russia’s Supreme Court Rewrites History of the Second World War,” EJIL:Talk!, 28 October 2016. |

| ↑30 | European Commission for Democracy Through Law (Venice Commission), Opinion No. 981/2020, 18 June 2020, “Russian Federation. Opinion on the Draft Amendments to the Constitution of the Russian Federation (Signed by the President of the Russian Federation on 14 March 2020) Relating to the Execution in the Russian Federation of Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights.” |

| ↑31 | Cynthia M. Horne and Lavinia Stan, eds., Transitional Justice and the Former Soviet Union: Reviewing the Past, Looking Toward the Future (Cambridge University Press, 2018); Eva-Clarita Pettai, “Prosecuting Soviet genocide: comparing the politics of criminal justice in the Baltic states,” European Politics and Society 18.1 (2017): 52–65. |

| ↑32 | Law No. 2538–1 (On the Legal Status and Honoring of Fighters for Ukraine’s Independence in the Twentieth Century); Law No. 2558 (On Condemning the Communist and National Socialist (Nazi) Totalitarian Regimes and Prohibiting Propaganda of Their Symbols); Law No. 2539 (On Remembering the Victory over Nazism in the Second World War); and Law No. 2540 (On Access to the Archives of Repressive Bodies of the Communist Totalitarian Regime from 1917–1991). |

| ↑33 | Ilya Nuzov, “Freedom of Symbolic Speech in the Context of Memory Wars in Eastern Europe,” Human Rights Law Review 19.2 (June 2019): 231–253. |

| ↑34 | “European Parliament resolution of 19 September 2019 on the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe (2019/2819(RSP) ).” |

| ↑35 | Jan Strupczewski, “EU raps Russia for saying Poland helped start World War Two,” Reuters, 15 January 2020. |