Photo © P.sanspeur

In 2019, after many years of discussion, the ILO adopted the Convention on Combating Violence and Harassment at Work. Why is this document called historical in its meaning and expected legal consequences?

In 2019, the ILO will celebrate its 100th anniversary. This agency was established to promote social justice; since then, setting international labour standards and monitoring their implementation has been its key strategy in advancing this goal. This work is far from completed; instead, it has become even more relevant in the context of sustainable development.

On 21 June 2019, at its 108th Centenary Session, the ILO adopted by an absolute majority its new Convention No. 190, complete with Recommendation No. 206, on eliminating violence and harassment in the world of work. The new labour standard has been hailed as historic in terms of its significance and expected legal outcomes. The Convention is the first-ever international treaty adopted with the aim of eradicating violence and harassment in the world of work. It is also the first convention adopted by the ILO since 2011.

Workplace safety is the foundation of equality, decent living, social justice and wellbeing of societies. The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) estimates that on average, 40%–50% of workers worldwide have experienced harassment. Moreover, according to World Bank estimates, some 500 million women of working age live in countries lacking legal safeguards from harassment at work: in 59 countries, women are not legally protected from workplace sexual harassment. Such lack of legal protection is observed in 70% of economies in the Middle East and North Africa, half in East Asia and the Pacific, and one-third in Latin America and the Caribbean.

To a large extent, the ILO Convention and Recommendation fill the global regulatory gap with regard to violence and harassment in the workplace by offering the widest, so far, range of measures against various unacceptable behaviours and practices, while taking account of potential changes in employment conditions and arrangements in today’s world and providing a significantly higher level of protection than the general provisions of existing instruments, such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

Convention No. 190 stipulates that the world of work should be free from violence and harassment and lays a framework for efforts to protect hundreds of millions of workers, especially women. This new standard is expected to help states, employers and unions to adopt adequate human resources policies, including specific measures to prevent violence and harassment and to remedy their adverse consequences.

Content of the ILO Convention No. 190 and Recommendation No. 206

The Convention defines the terms “violence and harassment” and proposes measures to prevent and combat them.

According to the Convention, “violence and harassment” in the world of work include a range of unacceptable behaviours and practices, or threats thereof, whether a single occurrence or repeated, that aim at, result in, or are likely to result in physical, psychological, sexual or economic harm, including gender-based violence and harassment.

Focusing in particular on gender-based violence, the Convention defines “gender-based violence and harassment” to mean violence and harassment directed at persons because of their sex or gender, or affecting persons of a particular sex or gender disproportionately, and to include sexual harassment.

The Convention potentially covers physical abuse, verbal abuse, bullying and mobbing, sexual harassment, threats and stalking, among other things. It recognises and promotes the right of everyone to a world of work free from violence and harassment. Based on the principle of inclusivity, this instrument protects everyone in the world of work, such as workers and other persons, including formal employees as well as persons working irrespective of their contractual status, persons in training, including interns and apprentices, workers whose employment has been terminated, volunteers, jobseekers and job applicants, and individuals exercising the authority, duties or responsibilities of an employer.

The Convention applies to all sectors, whether private or public, both in the formal and informal economy, and whether in urban or rural areas. The Convention also takes account of the fact that nowadays work does not always take place at a physical workplace; so, for example, it covers work-related communications, including those enabled by ICT.

The Convention is complete with a Recommendation which sets out practical measures to bring national practices in line with the Convention.

The full text of the Convention is available at the ILO website.

History of the new international labour standard

The process of drafting the Convention Concerning the Elimination of Violence and Harassment in the World of Work took some ten years and started off with the publication of the ILO’s special report “Gender equality at the heart of decent work” in 2009 which called to prohibit gender-based violence in the workplace and to take measures for preventing it. Over the years, a number of reports have been published which outlined the scope of the problem and its various manifestations, as well as the impact of violence and harassment on female and male workers, reviewed the relevant laws and practices in a number of countries, and offered recommendations for the content of the standard to be developed.

In October 2015, the Governing Body of the ILO finally decided to include the item “Violence against women and men in the world of work” on the agenda of the 107th Session of its Conference scheduled for June 2018. Prior to that, similar proposals had been submitted to the Governing Body at least five times 1According to the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), at least seven times.. In October 2016, this agenda item was renamed to “Violence and harassment against women and men in the world of work.” This updated agenda item was discussed for the first time at the 107th Session of the International Labour Conference in June 2018.

In August 2018, the ILO published a “brown paper” report entitled “Ending violence and harassment in the world of work,” which included the proposed texts of the Convention and its complementing Recommendation based on the initial discussion of this agenda item. The report was circulated to all ILO member countries for changes and comments, and feedback was received from delegates of 101 countries, including the governments of 57 ILO members, including EU countries such as Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Poland, Spain and Sweden, and the Russian Federation. Their comments informed the second discussion of the Convention in June 2019. Thus the ILO made a historic commitment to coordinate the positions of trade unions, employers and governments regarding the new labour standard, in accordance with its mandate approved 100 years ago.

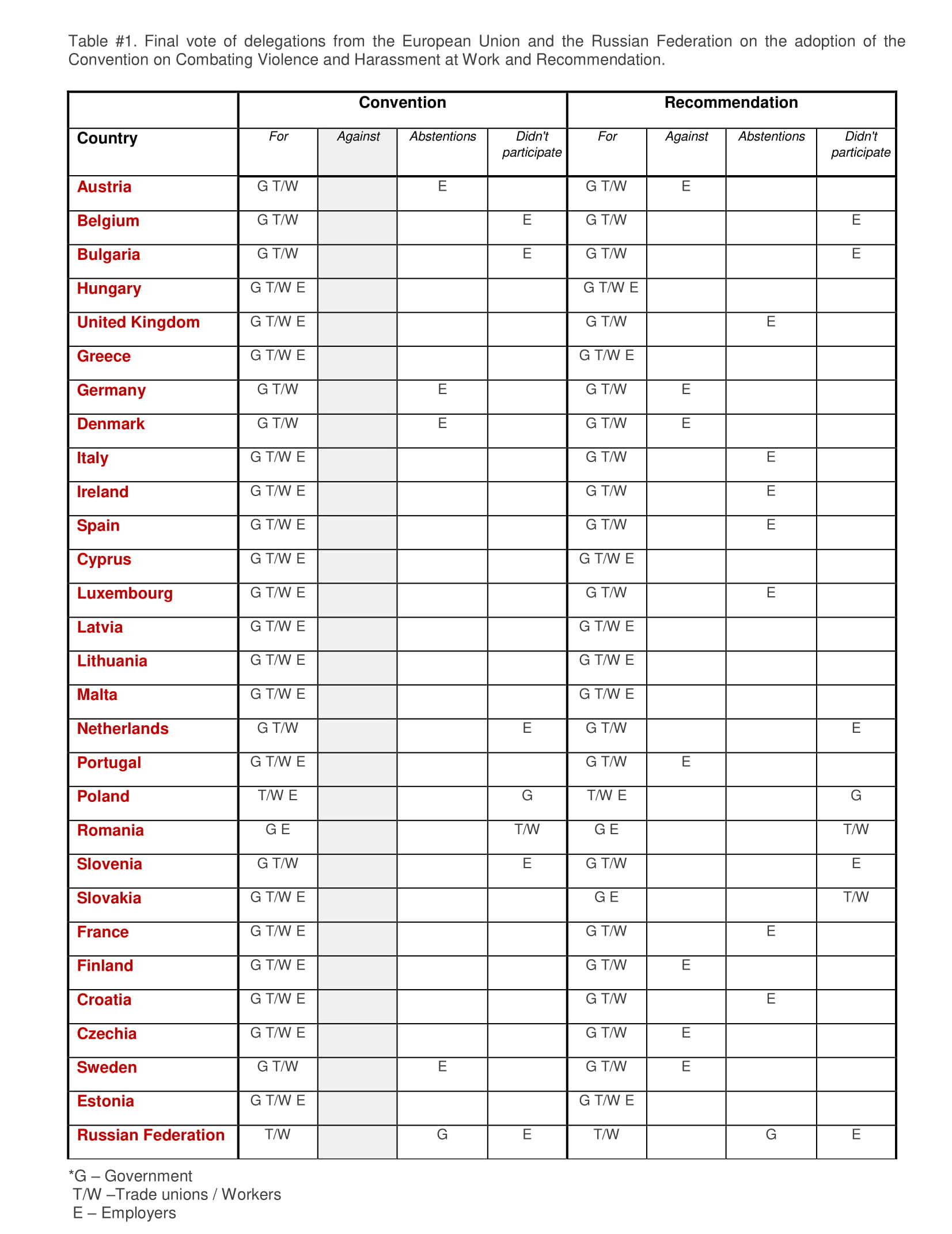

The final vote on the Convention and Recommendation took place on 21 June 2019 at the ILO Headquarters in Geneva. A two-thirds majority of votes of the International Labour Conference delegates was required for the Convention and Recommendation to be adopted. The government delegations of each member country have two votes, the trade union delegations have one vote and the employer delegations have one vote. The delegations voted as follows:

- Convention: 439 votes in favour, seven votes against, and 30 abstentions 2See final voting by the delegations here.

- Recommendation: 397 votes in favour, 12 against, and 44 abstentions 3See final voting by the delegations here.

None of the governments voted against the adoption of the Convention and Recommendation. See Table 1 for detailed information on the final vote of the delegations.

Significance and prospects of the new international standard

As with most ILO Conventions, Convention No. 190 will enter into force 12 months after two member States have ratified it 4See Article 14 of the Convention. The Convention is now open for ratifications. Given the high level of support, the first two ratifications may take place as early as in 2019-2020, and then the Convention will come into force in 2020-2021.

But the Convention will have an impact even before then. Once the standard is adopted, all member States, in accordance with Article 19 of the ILO Constitution, are required to bring the Convention and the Recommendation to the attention of their competent national authorities (usually the parliament) for considering relevant legislation or other measures. In the case of the Convention, this means its ratification. This ensures that the issues addressed by the Convention will receive visibility at national as well as international level.

The Convention will be legally binding only on those ILO member States which ratify it. Ratification is a sovereign act of a member State of the ILO expressing the State’s intention to be bound by the terms of an international labour Convention. Ratified standards are to be applied in law and in practice. Cooperation between countries to pursue social justice remains a pillar of the multilateral system. Ratification is a political act, as well as a legal act, in support of such cooperation.

Once ratified, a Convention generally comes into force for that country one year after the date of ratification. Ratifying countries undertake to apply the Convention in national law and practice and to report on its application at regular intervals. Technical assistance can be provided by the ILO, if necessary, to support countries in their implementation of a Convention. As part of the ILO system of supervision, a complaint may be filed against a member State for not complying with a ratified Convention.

Even those countries which do not ratify this Convention will be required, in accordance with the ILO Constitution, to report to the Director-General of the International Labour Office, at appropriate intervals as requested by the Governing Body, the position of their domestic law and practice in regard to the matters dealt with in the Convention, stating the difficulties which prevent or delay the ratification of the Convention.