Photo: Rasande Tyskar

How the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the lives of prisoners, disabled people, and refugees

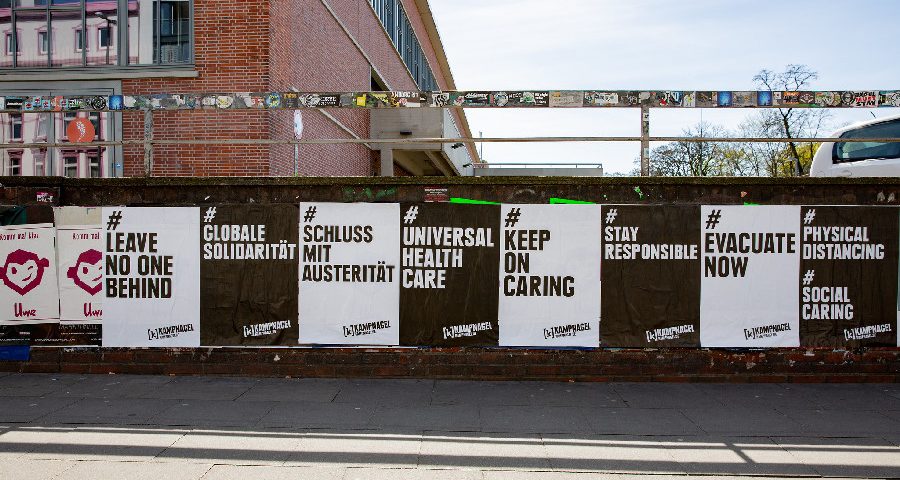

At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020, it seemed that we were all equally vulnerable to the coronavirus, which did not discriminate by gender, ethnicity, social status or income. Politicians said that we were all in the same boat. It soon became apparent, however, that this was not entirely true. People suffering from chronic ailments, the elderly, ethnic minorities, and people living below the poverty line have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic. People subject to confinement—prisoners, people with disabilities, and refugees—constitute a particular risk group. How has the coronavirus changed their lives? How have they been affected by the pandemic?

Barbed wire is no obstacle to the virus

When the coronavirus epidemic broke out in Italy in late February 2020, the country’s prisons were quarantined. Visits from family, friends, and social services were banned, and most activities inside prisons—such as educational courses, vocational training, and sports—were cancelled. The restrictions provoked dissatisfaction among prisoners. A wave of prison riots swept through the country in which twelve prisoners were killed. Although the riots were quickly quelled, the situation in the prisons has remained tense.

During the first wave of coronavirus, Italy’s penitentiaries avoided mass infection, but in the autumn of 2020, with the beginning of the second wave, the number of infected prisoners increased. In early November, more than 1,200 prisoners and staff in Italian prisons were infected with the coronavirus. According to Sofia Ciuffoletti, director of L’Altro Diritto, which provides legal assistance to prisoners, the increase in infections proved that the infection rate amongst the incarcerated was much higher than in the general populace.

According to Ciuffoletti, it is a big mistake to think that prisons are already protected from the coronavirus because they are closed institutions, seemingly cut off from the outside world. In reality, a lot of people, such as prison staff, go in and out of prisons every day. “When the virus gets in, it leads to disastrous situations.” says Ciuffoletti.

Prisons are overcrowded, dirty, and vulnerable

Overcrowding is the main reason prisons are vulnerable to epidemics. In December 2020, the total number of inmates in Italian prisons was in excess of 53,000, against a maximum capacity of 50,500. But the problem is global: the prison systems in more than 120 countries around the world are overcrowded.

Another reason is poor sanitary conditions. According to Ciuffoletti, in Italian prisons, there are three people on averaged in each twelve-meter-square cell. There is no ventilation and little sunlight, bed bugs tend to infest the beds, and the showers are designed for a much smaller number of people. In such circumstances, it is impossible to socially distance. Also, the health of prison inmates is, on balance, worse than that of people outside the prison system. Statistically, most prisoners come from impoverished socio-economic conditions, meaning that they most likely did not have full access to medical care. According to Ciuffoletti, many prisoners see a doctor for the first time in their lives when they are in prison.

Fear of public opinion and inaction on the part of the authorities

To prevent coronavirus outbreaks, it is not enough to simply close and quarantine the prisons. “Lockdown is something we cannot avoid. But it must be combined with other measures,” says Ciuffoletti. For example, she suggests a robust campaign to reduce overcrowding, alternative measures such as probation or house arrest, improved sanitation, a testing campaign, and giving inmates priority access to the vaccine.

All these measures are necessary to make the situation in the prison system less critical. “I visited a prison [during the coronavirus], and I can say that I have never seen so many psychological problems. People start to suffer from depression, go crazy, not being able to see anyone. They’re scared,” Ciuffoletti says. “They see that the outside world has no consideration for them. So, they feel like underdogs because they are sometimes treated like underdogs.”

Public opinion is often an obstacle to taking effective measures against the coronavirus in the Italian prison system: according to Ciuffoletti, Italian public opinion is negatively biased toward prison inmates. The populist government currently in power in Italy always follows the lead of the majority instead of protecting minorities. “There is the idea that when you’re in prison, you’re out of civil society, and you need to be stripped of all your rights. But this is social vengeance, a sentiment that should be avoided by the government,” she says.

Disabled people at risk

People with disabilities have also been at risk. Many of them live in group homes, psychiatric hospitals, retirement homes for older persons with disabilities, residential schools for children, and other residential settings. Their rights, as well as the rights of people with disabilities living outside institutions, have also been significantly restricted during the pandemic.

The COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor survey, published in October 2020, lists numerous violations of the health rights of disabled people due to the pandemic. Most of the facilities surveyed had been quarantined, and residents were trapped inside without access to family, friends, or human rights advocates. Quarantine measures had not been discussed with the residents themselves, although residents of many institutions usually have a voice in resolving such issues. Disabled people living outside of institutions also faced problems: many of them had lost access to essential services—for example, 38% of the people surveyed had been living without personal assistance. This led to isolation and the fact that, for many, their survival depended entirely on the support of families, NGOs, and charities. Access to information was also limited: information about the pandemic or quarantine restrictions was often not provided in a form accessible to disabled people, for example, in sign language or easy-to-understand language. It has also become more difficult for them to get medical care, including for ailments unrelated to COVID-19.

Triage: who lives, who dies?

Ursula Naue, a senior lecturer at the University of Vienna and a member of the expert group on the implementation of the Austrian National Action Plan for Persons with Disabilities 2012–2020, believes that the pandemic has highlighted the huge gap existing between the rhetoric of human rights and its implementation in practice. Naue argues that the most striking example of violating the rights of the disabled is the practice of triage in hospitals. When the health system’s resources are exhausted, and there are not enough places in the ICU for everyone, hospitals are forced to decide whom to treat, and whom to leave for dead.

Naue emphasises that disabled people are systematically less likely to receive medical care during triage, regardless of their actual health. After all, one of the important criteria for triage in Austrian hospitals is the activity of daily living (ADL) score, which takes into account how a person copes with everyday tasks—for example, brushing teeth and moving around. If a person is healthy, but cannot perform such tasks, for example, due to cerebral palsy, it is quite likely that they will not be admitted to the ICU and thus will not survive COVID-19.

Disability and illness are not the same thing

According to Naue, this approach blurs the distinction between disability and illness. People with disabilities are not necessarily ill. They have certain impairments in which some parts of the body do not function as they should. Sometimes such impairments lead to diseases; sometimes, on the contrary, diseases cause impairments, but they are still not the same thing. Therefore, triage procedures would be fairer if they took into account only the actual state of a person’s health. An even better alternative would be to provide care to people as they arrived, meaning that the first to arrive would be the first to be admitted to the ICU. In any case, it is vital that there is a public discussion of the selection criteria, because there are still no legal regulations governing the procedure.

“There’s a century-long tradition of perceiving persons with disabilities as ones who need charity but have no rights. This is now very obvious in the context of triage. Because we still think that persons with disabilities are not deserving, because they are not part of work, employment and so on. Nowadays there’s a kind of hierarchy of rights: there are the rights of persons without disabilities, and then there are the rights of persons with disabilities,” says Naue.

Refugee camps in lockdown

A similar disparity of rights has been observed vis-à-vis refugees, especially in the so-called hotspots (accommodation centres) on the Greek islands. Living conditions in the camps, already infamous for their overcrowding and blatant human rights violations, have only worsened during the pandemic.

Just as the Italian authorities did in their country’s prisons, the Greek government decided to restrict freedom of movement in the camps even before cases of COVID-19 had been detected, and when the first cases did appear, the camps were completely locked down. Thousands of refugees were effectively trapped in overcrowded camps with a complete lack of basic hygiene and the inability to socially distance themselves. Although a small number of particularly vulnerable asylum seekers were evacuated, the accommodation centres on the islands remained overcrowded. (In April 2020, they held 34,000 people, despite the fact that they are designed for six thousand people.) People in the camps live amidst rats, snakes, and garbage, often in canvas tents and makeshift huts. They have to queue for hours to get food, water, or go to the toilet. In addition, overcrowding and police inaction have generated an atmosphere of chaos and violence in the camps, and women there often fall victim to sexual harassment and violence.

Lack of medical care

Such living conditions have disastrous effects on the psychological health of asylum seekers. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, the number of refugees in Greece experiencing psychotic symptoms—such as hallucinations and delusions—has increased by 71%, according to a study by the International Rescue Committee (IRC). Of the 904 people who received psychological help from IRC staff, 41% had PTSD symptoms, 35% had suicidal thoughts, and 18% had attempted suicide. “In Afghanistan we were afraid of suicide bombers and I thought leaving there would be my salvation. But it is worse here… I have witnessed many suicide attempts [here]. I even tried to hang myself but my son saw me and called my husband,” Fariba, 32, from Afghanistan, told the IRC.

Not only the mental, but also the physical health of the refugees has been under threat. Elli Kriona-Saranti, managing attorney at HIAS Greece, which provides free legal aid to asylum seekers on the island of Lesvos, explains that basic medical services were not readily available on the islands even before the pandemic’s outbreak, but the lockdown has made it even more difficult to get medical care. She is aware of cases of HIV, cancer, hepatitis, and serious psychiatric problems that have deteriorated considerably during the long wait for medical care. The camps are located in border regions with poor infrastructure, and for the treatment of many diseases—for example, antiretroviral therapy for HIV—refugees must be transported to the mainland. Due to the restrictions imposed on them, however, they are not permitted to leave the islands, and the process of getting the restrictions waived can take months.

One of the cases that the Kriona-Saranti’s organization dealt with was the case of a girl born with a heart defect. In late January 2020, the hospital demanded that the child be immediately transferred to Athens in order to undergo an emergency operation that could not be performed on Lesvos. In mid-April, the child died in the Moria camp, since the restrictions on her movement had never been lifted.

Kriona-Saranti believes that although the pandemic has worsened the circumstances of refugees due to quarantine measures and their inability to leave the camps, they had been critical before. In her opinion, closing the camps and abandoning the “hotspots” strategy is the only way to ensure decent living conditions for refugees. But it is just this strategy that the Greek government and the EU continue to rely on: the new EU Migration and Asylum Pact, unveiled by the European Commission in September, further toughens the procedure for obtaining asylum and makes possible a repeat of the disaster on Lesvos. Almost a year after pandemic’s outbreak, the situation of refugees—as well as that of prison inmates and the disabled—remains precarious.

This article is based on the Legal Dialogue online symposium “It’s time to rise and shine: Legal response to the impact of the pandemic,” December 2020.